This St. Patricks’ Day, we will continue our series looking at some important Irish transport engineers throughout history. Previously we’ve examined the work of Henry Ferguson and James Drumm, but this year the focus will be on John Phillip Holland, one of the most influential figures in maritime innovation. Like all great historical romps, the story of John Holland starts out in meagre environs, encompasses religion, war and rebellion, double deals, unlikely successes and disappointing setbacks, before ultimate triumph and global renown and recognition, and the establishment of one of the world’s largest defence companys.

The Dreaming Schoolteacher

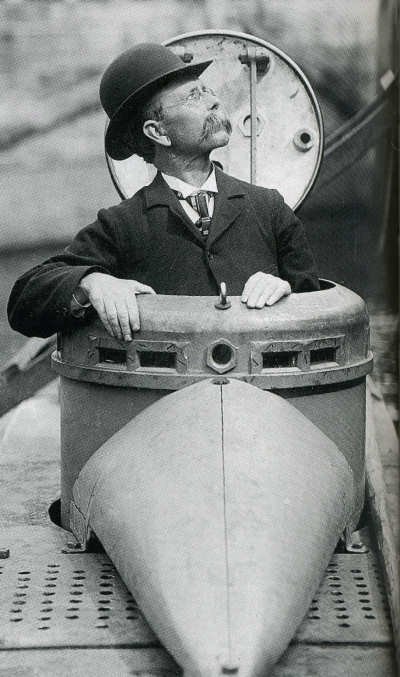

John P. Holland was born in 1841 at a coastguard cottage on the shores of the Atlantic, in Liscannor, Co. Clare, close to the Cliffs of Moher. Hollands’ early life was dominated by marine activity. His father was a member of the local coastguard, working as a boatman. When aged 12, his father died and the family moved to the city of Limerick. Holland is enrolled in a local Christian Brother’s School, where he begins a journey that sees him join the Christian Brothers to become an educator. He begins a career teaching in various centres around Ireland, including Limerick, Dundalk and Cork. In 1862, the Cork Examiner report on the American Civil War battle of Hampton Roads between the CSS Virginia and USS Monitor (the first battle of Ironclad ships) reportedly inspires Holland to begin designing submarine vessels. In 1873, Holland moves to Boston, USA, and a year later takes up a teaching post in Paterson, New Jersey, which was a growing city dominated by Irish arrivals. In 1875, Holland makes a formal application to the US Navy for his submarine design, but is rejected, with the Navy unhappy with a lack of visibility in the design and the professional profile of the designer (“a civilian landsman”).

A Revolutionary Twist

The Holland 1 was built in a Paterson workshop, and launched in front of a large audience in the local Passaic River. However, some missing screw plugs were supposedly to blame for a rather ignoble maiden voyage. Shortly after this, Holland uses some family contacts to the Irish Republican Brotherhood organisation (also known as the Fenians) to seek another audience for his idea. The relationship moves forward, and the local IRB agree to fund a further prototype. This prompts the once religious brother to quit his teaching post, and pursue his fortune in creating covert weapons for a revolutionary movement. The vessel is envisioned to be used against the British Navy, launched from a cargo ship, carrying three men. Holland went to great lengths to keep this creation secret, but a report of “the Fenian Ram” is carried in the New York Sun.

The boat (officially the Holland 2) is built in New York, and launches in 1881. It is successfully trailed and improved, but the relationship between Holland and the Fenians has run aground. The original boat goes missing from it’s New Jersey dock, and is later found in New Haven, Connecticut. However, the new “owners” lack the necessary operating skills, and the vessel sinks in New Haven harbour. Payments are not completed, and Holland severs all links with the revolutionaries.

Navy Contract Wins

Holland uses his experience in designing and testing the Holland 2, to submit designs for US Navy competitions, and is finally successful in winning a contract. He forms the John Holland Torpedo Boat Company in 1893. The resulting vessel (the Holland V), however, is subject to a number of design requirements imposed by the Navy including steam power, which Holland deems unnecessary and unworkable. He therefore takes it upon himself to design an alternative vessel (the Holland VI) which was powered by a gasoline engine and electric motor. The design allowed for the gas engine to power the ship for surface running, while charging the battery for submerged running. This hybrid powertrain design, along with a number of control innovations for precise steering and depth adjustments, marked the Holland VI out as the first modern submarine. The Holland IV was launched on St. Patricks’ Day 1898 in New York Harbour, and gained a recommendation from one Theodore Roosevelt, a Secretary of the Navy. The Navy was eventually convinced, and commissioned the ship as the USS Holland in 1900, the first modern submarine of their fleet. By now, Holland has merged his company with another, to form the Electric Boat Company, and this company goes on to build a further seven vessels according to this design, establishing an Atlantic and Pacific US Navy submarine fleet.

International Success

A similar design was also commissioned by the British Royal Navy, and the HMS Holland 1 was launched in 1901. This was built in Barrow-on-Furness in the UK, with design input from John Holland. In total five such vessels were built, and established the Royal Navy submarine fleet. His designs are also sold to the Japanese to launch their own submarine fleet, and these are used in a war with the Russia in 1904 and 1905. The initial five boats were built in the US, and final assembly took place in Japan. He later worked directly for the Japanese Navy to design and construct two further vessels. John Holland is recognised by the Emperor of Japan and awarded the Rising Sun for his contributions to the Japanese Navy. Holland’s designs were also sold to the Russian and Dutch Navies, through the Electric Boat company.

Final Years

In 1904, Holland parts ways with the Electric Boat company, but uses his designs on work for the Japanese Navy. This leads the Electric Boat company to place an injunction on Holland for patent infringement in 1905, and Holland is prevented from further submarine design activity. Instead, he devotes his time to a new form of transport, flying. Here he registered some patents related to elevation and control, ideas which seem familiar to the breakthrough technology that had served the submersible machines so well. However, owing to advancing years and ill health, he was unable to realise these ambitions, and finally passed away at his family home in Paterson, New Jersey in 1914.